Projecting the Impact of a Rent Freeze

New York City has roughly 2.3 million apartments. Roughly one-million of these units are rent-regulated, with an estimated 996,000 stabilized. The rest of the units are market rentals (1,139,000), public housing (178,700) or other rentals (52,810), which are typically affordable units financed by the government in some way that are not categorized as rent stabilized.

There has been a proposal by Zohran Mamdani, the Democratic nominee for mayor of New York City, to freeze the rents for the estimated 996,000 stabilized apartments for the next four years. These freezes would be implemented by his appointees to the Rent Guidelines Board (RGB) and would take effect starting on October 1, 2026 and last until September 30, 2030.

The average rent for stabilized apartments was $1,599 in 2023 and is estimated to be around $1,680 by October 1, 2026. The median rent in 2023 was $1,384 and is estimated to be around $1,455 at the start of the proposed rent freeze.

Average operating costs for rent stabilized apartments were $1,160 in 2023. They are currently estimated to be $1,292 based on the RGB’s Price Index of Operating Costs.

If RGB listed costs continue to rise at the current rate, and rents are frozen, this is the projected impact on rent-stabilized housing.

The amount of revenue leftover after RGB calculated operating costs is referred to as Net Operating Income. This is not profit. The RGB describes NOI as: “the amount of money an owner has for financing their buildings; making capital improvements; paying income taxes and taking profits.”

In most cases, roughly 80% of net operating income goes to building financing. This is true for privately owned buildings as well as non-profit housing and social housing. Under the rent freeze projection outlined above, the majority of rent-stabilized buildings would no longer be able to pay their debt service, leading to a massive foreclosure crisis and significant physical deterioration of this vital housing stock.

The Rent Stabilization Law has a provision to apply for hardship, which allows buildings to raise the rents by up to 6% a year above the adjustment put forth by the RGB. Under our projection, roughly half of rent-stabilized buildings would be eligible for alternative hardship by 2030.

Case Study 1: 45-Unit building on Elliot Place in The Bronx

Analysis:

Like many buildings in the Bronx, this privately-owned and 100% stabilized building has seen operating costs and property taxes rise over the past five years, eliminating all of its net operating income. In 2024, the building had $29,160 in operating income for the entire year. This was not enough to cover the estimated $37,800 in debt service payments. There was no money to pay for mandatory capital costs.

In the past five years, the building has been systemically defunded by rising expenses and capped rent increases. In 2019, average rents in the building were $987. Average costs and taxes were $865. That resulted in a net operating income of $65,880, which, adjusting for inflation, would be $80,911 in 2024 dollars or 177% more than the current operating income.

At this point, all of the building’s rental income is being invested directly back into the building operations. The declining operating income means the building has no access to additional capital and is unable to make mandatory upgrades. The result has been increasing violations and physical decline.

Rent Freeze Model:

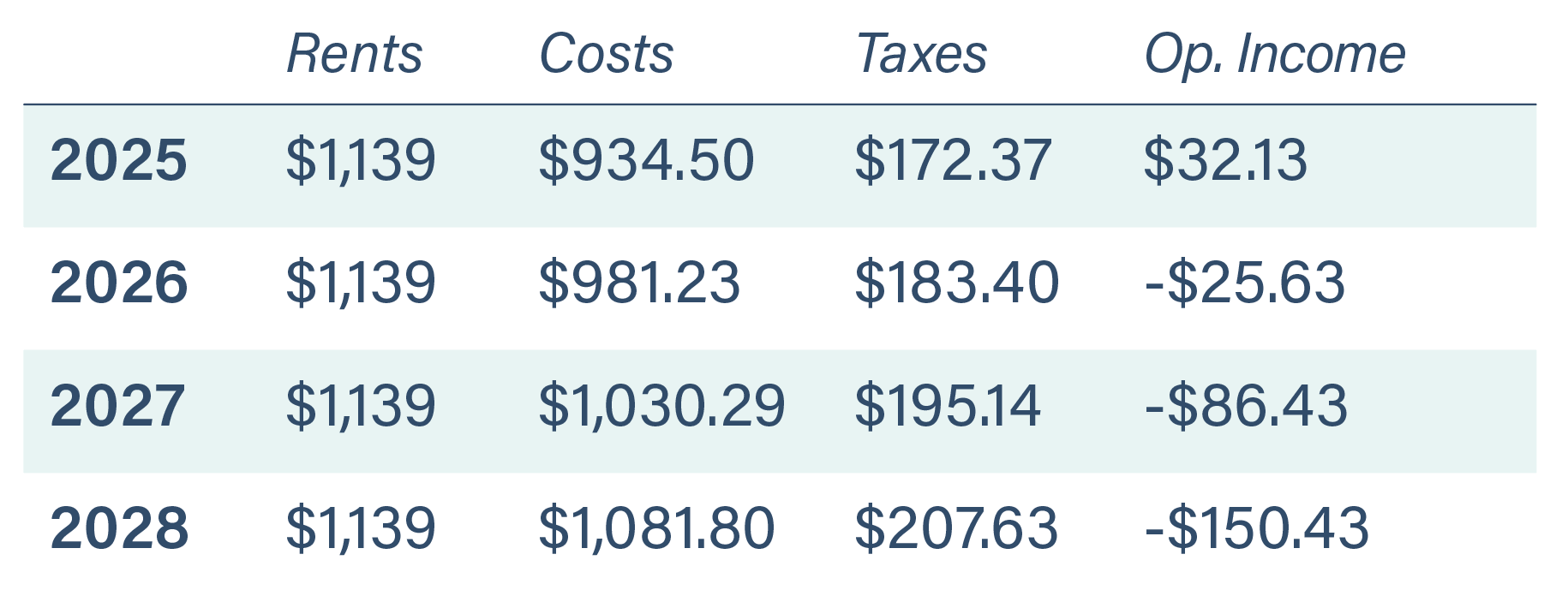

The proposed rent freeze would go into effect on October 1, 2026. Average rents for this building would be an estimated $1,139 for the next four years.

Historically, operating costs rise by 5% annually, and property taxes for this building have increased by an average of 6.4% annually. If this continues for the next four years, we can model the operating income.

Starting in year one of a rent freeze this building will begin to lose money. Even if the taxes were frozen on the building, it would also lose money. Historically, tax assessments rarely ever decline on buildings, but the unprecedented move of freezing rents might force the NYC Department of Finance to reduce building assessments.

Adjusting to Rent Freeze:

Facing the inevitability of financial loss it is very likely that the building will have to find ways to reduce costs where possible. Typically the first expense to be cut back is spending on repairs and maintenance. Buildings may also reduce labor costs, resulting in slower response times to renters’ concerns. Eventually, as the building falls deeper into financial distress, they will likely be forced to miss mortgage payments or stop paying property taxes.

The building could file for alternative hardship with the state Department of Housing and Community Renewal. Typically these applications take two or three years before a successful verdict, at which point the rents may be adjusted upward by no more than 6% a year. In the case of this building, it may be eligible for hardship relief starting in 2028, allowing them to raise rents to $1,207 at most. This would reduce the building’s estimated operating deficit from $150 per apartment to $82 per apartment.

It is important to note that in order to be eligible for hardship the property owner would have to spend tens of thousands of dollars on lawyer fees to handle the application process. The owner also has to go through the expensive and time consuming process of removing violations on the building that have already been fixed. Due to backlogs at HPD, appropriate paperwork and follow up inspections to remove violations that have been cured can take years.

Historically, building owners do not file for hardship because of the costs associated and the bureaucratic uncertainty. Also they have to forgo their rights to challenge their property tax assessments. Starting a tax challenge immediately pauses any hardship application, restarting the clock on relief.

Case Study 2: 57-Unit building on 30th Road in Astoria, Queens

Analysis:

This 1927 building has 35 stabilized apartments and 22 market rate apartments, roughly a 61% to 39% split. The market rate rents in the building are 30.4% higher than the stabilized rents.

Over the past five years the Rent Guidelines Board has adjusted stabilized rents by 12.75%, which has been 6.15% below inflation. This has forced the building to more aggressively raise rents on market rate units (34.3%) in order to cover growing operating costs and mandatory capital improvements.

This is common practice in buildings that have a mix of stabilized units and market rate units. In years when the RGB has adjusted rents below inflation, the other units in the building have seen higher rent increases. In years when the RGB has increased rents near or above inflation, the rents in market rate units typically have increased about the same as stabilized units.

Rent Freeze Model

Applying the same methodology as Case Study #1, we calculated expected rent increases in 2025, 5% annual increases in expenses, and 6.4% annual increases in property tax assessments. In this scenario, we apply an 8% increase on market rate rents due to the passage of Good Cause Eviction, which limits rent increases to 5% plus the Consumer Price Index.

In 2021, the difference in rents between stabilized units and market rate units in this building was 29.2%, with stabilized rents at $1,425 and market rents at $1842. Under this simulation, the difference will grow to 69.1% as the 22 market units are relied on to cover all of the building’s cost increases. At the same time, operating income for the building will decline, which in turn will lower the value of the building and put it at risk of making its mortgage payments and likely leading to deference of mandatory capital expenditures.

Adjusting to Rent Freeze:

The building owner will likely raise market rents as much as possible, capped at an estimated 8% annually, instead of the 4% to 5% that they were raised for the previous four years. This would be necessary to offset the expected increases in operating costs and taxes, allowing the building to maintain operating income to pay off debt service.

It is possible that market forces would limit the ability to increase rents aggressively, forcing the building owner to either absorb the operating income decline or adjust operations in an attempt to maintain a healthy net operating income and keep up with mortgage payments. Due to high interest rates there is a good chance that the mortgage payments on this building would actually need to increase, or the building owner would need to find new capital in order to secure a loan.