Voters Say Housing Is Broken

Exclusive Poll: 61% of New Yorkers say current housing policy is making things worse, not better”

The first step towards solving a problem is admitting there is a problem. For the past several years there have been countless politicians who have said New York is in a housing crisis. There have been some solutions proposed, a few things have passed, and occasionally elected officials have patted themselves on the back for these developments. But despite everything that has been done over the past decade, voters have continued to sour on housing policy.

In August, the New York Apartment Association commissioned a poll on housing policy in New York City. Speaking to 1,000 voters, we found that there was near universal agreement on one thing: housing is broken.

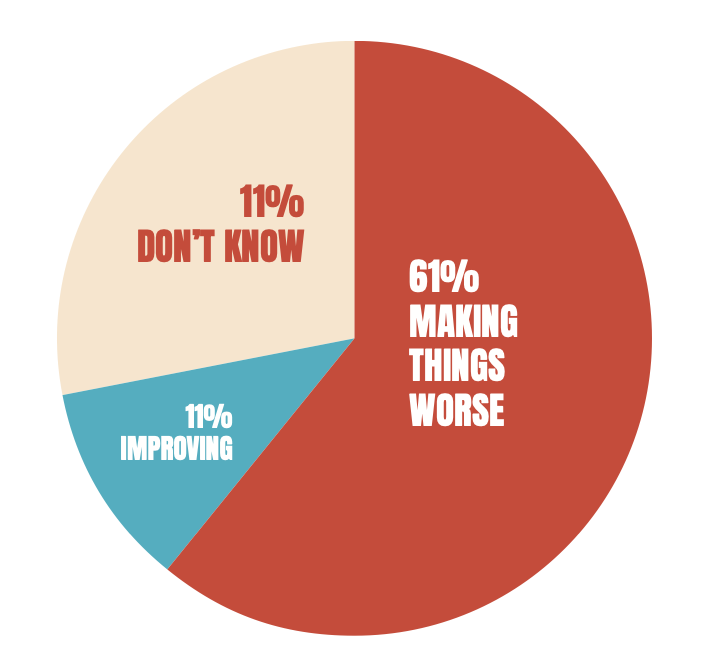

We specifically asked the voters if they believed the current housing policies and rent regulations are helping to improve housing or are they making things worse. The results were overwhelmingly negative, with 61% of respondents saying the government is making things worse and only 11% saying policy is improving the situation.

The disapproval with housing policy was bipartisan with 62% of Democrats saying policy is making things worse, along with 66% of Republicans and 55% of independents. Younger voters, between 18 and 39, were the most upset with housing policy with 66% saying they were making things worse. A majority of older voters, over 65, also said politicians were making things worse at 54%.

“What was potentially the most eye-opening response came from rent-stabilized tenants who were surveyed. Among this group, 65% said that housing policy and rent regulations were making things worse and only 12% said politicians were improving the situation.”

One of the reasons the vast majority of voters think things are getting worse is what they are seeing. We asked if the number of affordable apartments had increased or decreased in recent years and 48% said it decreased, with only 19% saying the number had increased.

In the past ten years, the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development reports that they have created about 67,000 affordable homes. They also say they have preserved about 135,000 affordable homes. Preservation projects generally focus around the government providing subsidies to nonprofits to take control of failing apartment buildings. While rescuing these buildings is a vital part of the city’s efforts to preserve affordable housing, it is expensive and pulls resources away from creating new supply.

From 2010 to 2023, the overall supply of housing in New York City grew by an estimated 307,000 or about 7.4%. This may sound like an achievement, but the national average for housing growth in that time was 10.3%, which was still not enough to keep up with population growth in the country.

The result of failing to build enough new housing and spending so much of the city’s resources on rescuing failing buildings has been that supply has not kept up with demand. That leads to more competition for available apartments, higher rents and bidding wars, and more frustration for renters.

Renters in stabilized apartments with below market rents often feel trapped. They may want to move to another neighborhood in the city that is closer to their job, or their family, but they cannot find an apartment with a similar rent in their desired location. Rent control policies have long been criticized for the chilling impact they have on the dynamic movement inside a city. Economic studies show that over time the policy creates a divide in the rents paid by tenants who remain in place and the vacant units available for rent. In 2024 in New York City, the average apartment rent was estimated to be around $1650, while the average asking rent for a vacant unit was $3,400 or more than twice the average rent paid.

Reforming rent-stabilization to allow for more mobility for tenants may be a way for elected officials to improve the public opinion of current housing policy. Our poll found that reform is desperately desired.

We asked voters if they think housing needs “a lot of reform” or “some reform” or “little reform” or “no reform”. The majority of respondents told us that a lot of reform was needed, 54%, with 25% saying some reform was necessary.

Interestingly, rent-stabilized tenants were some of those asking the most for reform with 70% saying housing policy needed “a lot of reform”. An additional 16% said policy needed “some reform”. Only 5% of rent-stabilized tenants said no reform was needed.

The desire for changes from the majority of rent-stabilized tenants, just six years after the state legislature made significant changes to the laws, call into question the effectiveness of the reforms. Clearly rent-stabilized tenants overwhelmingly still feel that the rent laws are failing them.

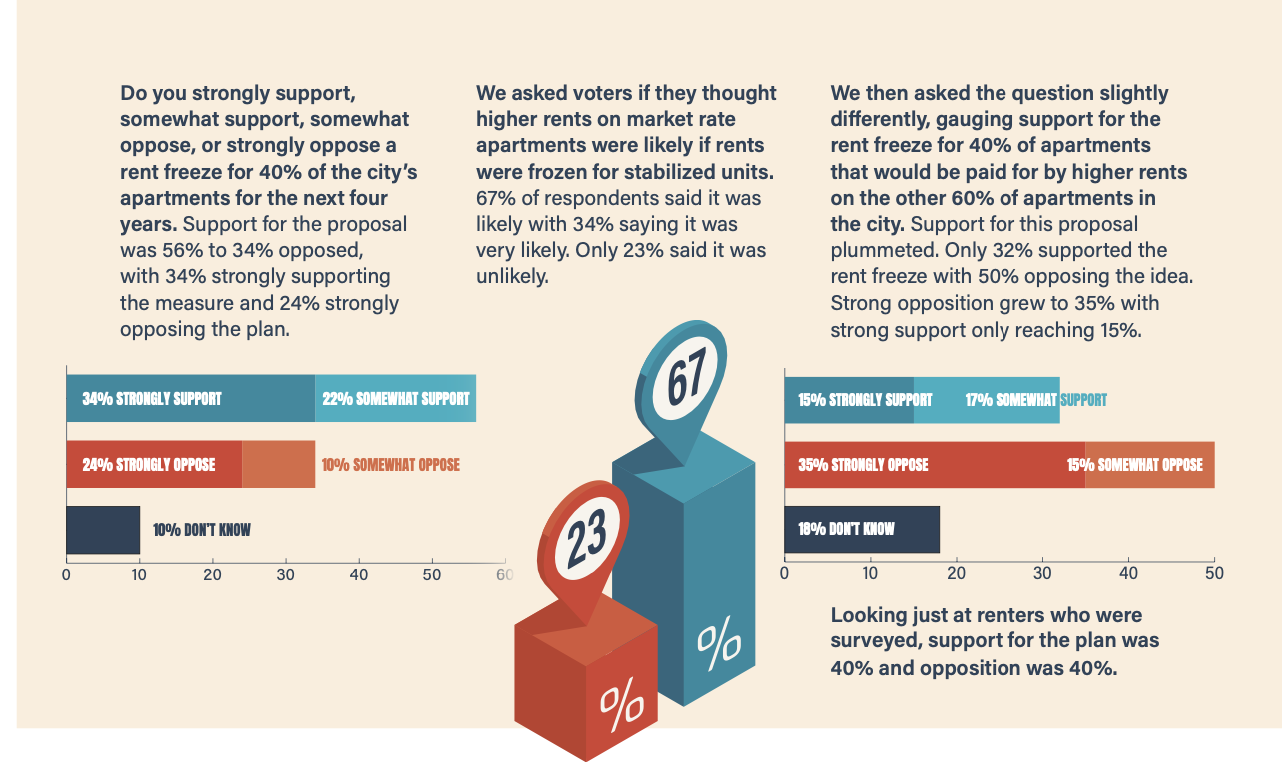

Our polling also looked at the proposal to freeze rents for roughly one-million stabilized apartments in New York City. Instead of mentioning the number of apartments, we asked voters if they supported a rent freeze for 40% of renters, which is equal to the one million stabilized apartments. Among all voters 58% supported this rent freeze. Among stabilized tenants, 65% supported the rent freeze.

We also asked renters if they believe freezing rents for 40% of renters would lead to higher rents for the other 60% of renters. Two-thirds of respondents said this was likely to happen. Economic studies have repeatedly shown that rent control schemes which impact a portion of rentals lead to a large gap in rents. In New York City, median regulated rents are around $1500, while asking rents for market rate units average well over $3,000. Recently, NYAA visited a building in the East Village that had a $502 rent control unit across the hall from a market unit with a $5,000 rent. Down the hall was a stabilized apartment with a rent of $906.

We then asked voters if they would support a rent freeze for 40% of renters if it meant rents will increase faster for 60% of tenants. Support for the rent freeze proposal dropped to 32% support and 50% opposed. Among just renters, support for the plan was 40% support and 40% opposed.

The debate over a rent freeze has accelerated after it became a focus of the New York City mayoral campaign. Over the past decade, the New York City Rent Guidelines Board has adjusted rents below inflation. Under the de Blasio administration, the rent adjustments averaged 0.65% below inflation annually.

Under the Adams administration the rent adjustments averaged 1.3% below inflation annually. During that time, property taxes have increased at roughly 30% faster than inflation and insurance costs have risen at roughly 85% faster than inflation.

In 100% stabilized buildings, a below inflation rent adjustment forces the building to reduce spending on maintenance and repairs, especially when property taxes and insurance premiums increase rapidly. This is the reason that roughly 5,000 rent-stabilized buildings housing more than 200,000 apartments are functionally bankrupt, meaning that the rental income fails to cover basic costs.

In their 2023 data, the most recent available, the Rent Guidelines Board outlined that net operating income had mostly stayed flat for older rent-stabilized buildings that do not receive any government subsidy. A closer look at the data found that the reason net operating income did not shrink was due to a significant pullback in spending on maintenance, which is a key indicator that physical distress is likely to increase rapidly in the next few years.

Housing experts at NYU Furman Center, the Citizens Housing Planning Council, and the Citizens Budget Commission have warned that the trend of defunding older rent-stabilized housing has put this key housing stock at dire risk. Their analysis is that if immediate change is not made to preserve this housing, it likely will be lost forever.