A System Under Strain

Rising Insurance Costs for Affordable Housing Have Reached Crisis Levels

New York lawmakers are sounding the alarm. At a joint public hearing held on November 18th, three State Senate Committees—Housing, Construction, and Community Development; Insurance; and Investigations and Government Operations—came together to confront a problem that has been quietly destabilizing the state’s housing market: the rising cost and shrinking availability of residential property insurance. The hearing followed a formal investigation launched in August 2025, in which lawmakers demanded detailed information from the Department of Financial Services (DFS), insurance associations, and carriers in an effort to understand the forces behind the sharp escalation in premiums.

The findings pointed to a slow-moving crisis. Although New York has not yet plunged into the turbulence gripping states like Florida or California, key sectors—particularly affordable housing, supportive and senior residences, and older multifamily buildings—are feeling acute strain. Premiums have soared, coverage options have narrowed, and more properties are being pushed into the costly surplus lines market. The consequences extend far beyond policy rates, threatening affordability, financial stability, and the long-term health of neighborhoods.

A Rare Gathering of Voices

The hearing drew one of the most diverse coalitions to weigh in on the state’s insurance landscape in years. DFS and NYC Housing Preservation & Development (HPD) shared insights alongside nonprofit housing providers, mission-driven developers, preservation groups, and associations representing large multifamily portfolios such as NYAA, BRI, and SPONY. They were met with testimony from insurers, brokers, and national industry associations, balanced by plaintiff-side trial lawyers, consumer advocates, climate experts, and equity organizations. Together, they painted a comprehensive picture of a system struggling under the weight of compounding pressures.

Where Lawmakers Pressed Hardest

Senators drilled into the central questions driving public concern. Why have premiums doubled or tripled in so many cases? Why are neighborhoods like The Bronx facing widespread nonrenewals? And how are older multifamily buildings—often the backbone of New York’s affordable stock—being evaluated by insurers?

The liability environment became one of the hearing’s flashpoints. Industry representatives blamed soaring claim costs, large settlements, and the longstanding Scaffold Law. Trial lawyers fired back, arguing that insurer practices—including delays, denials, and a lack of transparency—inflate costs more than litigation does.

Other testimonials addressed the broader societal trends influencing claim frequency. This included a focus on a growing number of lawsuits, the expanding role of injury-focused trial lawyers, and shifting attitudes about liability and compensation. One nonprofit insurance provider estimated that slip and fall cases are “pulling nearly $4 billion out of the housing stock” annually.

Another major concern was the state’s inability to access granular, claim-level data. Without it, lawmakers argued, DFS cannot assess whether New Yorkers are subsidizing losses in other regions, whether catastrophe models are aligned with actual risk, or whether underwriting criteria disproportionately affect certain communities.

These concerns fed into deeper questions about potential discrimination. Legislators pressed regulators and industry actors on whether underwriting patterns penalize rent-stabilized communities, voucher holders, and low-income neighborhoods—raising the specter of modern-day redlining disguised as risk assessment.

Climate and global market forces also loomed large. Stakeholders acknowledged that while New York has avoided the massive disasters seen elsewhere, it is not insulated from global reinsurance volatility, climate-driven catastrophe losses, or rapidly rising construction costs—all factors that insurers say are now baked into premiums statewide.

For those unfamiliar with reinsurance, it is a product that insurance providers purchase from large banks or private equity, to protect their business from failing to pay out extremely high premiums. When global disasters increase the cost of reinsurance, it has a direct impact on all insurance premiums, even if the policies are written in places without high risk.

What the Testimony Revealed

As testimony unfolded, a unified theme began to take shape: nearly every sector is feeling squeezed, albeit in different ways.

Regulators described a market that remains relatively stable overall but contains pockets of acute distress—particularly among older buildings and affordable housing. They highlighted ongoing efforts to modernize modeling, enforce anti-discrimination rules, and incorporate climate risk into regulatory frameworks, while acknowledging that limited access to data continues to hamper oversight.

Housing providers and nonprofit owners delivered some of the most urgent warnings. Insurance costs have become one of the fastest-rising and most destabilizing expenses in the sector. For many, premiums now consume 16–22% of gross rents. Some properties have experienced 300–500% increases. Maintenance is being deferred, refinancing is stalling, and operating deficits are widening. Many urged the state to explore reinsurance support, liability reform, and incentives tied to building upgrades that reduce long-term risk.

Insurance industry representatives framed the crisis as part of a broader national and global market recalibration. They pointed to construction inflation, climate-linked disasters across the country, reinsurance shortages, and New York’s own aging building stock as the main drivers of cost. They urged lawmakers to reform the Scaffold Law, streamline DFS rate approvals, and require more robust mitigation measures from building owners.

Trial lawyers countered that insurers’ narratives mask deeper issues—chief among them, insufficient transparency and weak accountability for unfair claim practices. They argued that without stronger consumer protections, claim-level reporting, and bad-faith remedies, policyholders will continue bearing the brunt of insurer-driven cost escalations.

Meanwhile, advocates for low-income homeowners and tenants highlighted the human impact: rising premiums that threaten homeownership, shrinking coverage that leaves families unprotected, and a looming risk that insurers may retreat from vulnerable neighborhoods unless the state invests substantially in resilience and smarter land-use planning.

Where Everyone Agreed

Despite profound differences in perspective, the hearing revealed several shared truths:

Premiums are rising sharply while coverage shrinks, with older multifamily and affordable housing hit hardest.

Multiple forces—climate risk, liability exposure, construction inflation, and reinsurance volatility—are converging, even if stakeholders disagree on which matters most.

Data gaps remain one of the biggest obstacles, leaving regulators, lawmakers, and the public unable to fully understand or address market behavior.

Solutions will require a multifaceted response, including targeted legal reforms, resilience investments, state-backed reinsurance options, stronger consumer protections, and incentives for risk-reduction measures.

Housing Provider Testimony (NYAA, SPONY, and BRI)

Across New York’s residential housing sector, the message from property owners—large and small, nonprofit and private—is unmistakable: the state is in the middle of an insurance crisis that is destabilizing rent-stabilized and affordable housing. The New York Apartment Association (NYAA), representing more than 400,000 units of pre-1974 rent-stabilized housing, delivered sweeping and urgent testimony, describing a market in which premiums have more than doubled, coverage has collapsed, and insurers are fleeing entire neighborhoods. Supporting testimony from the Building & Realty Institute (BRI) and the Small Property Owners of New York (SPONY) confirmed that the crisis is statewide, affecting large portfolios, co-ops and condos, and mom-and-pop owners alike.

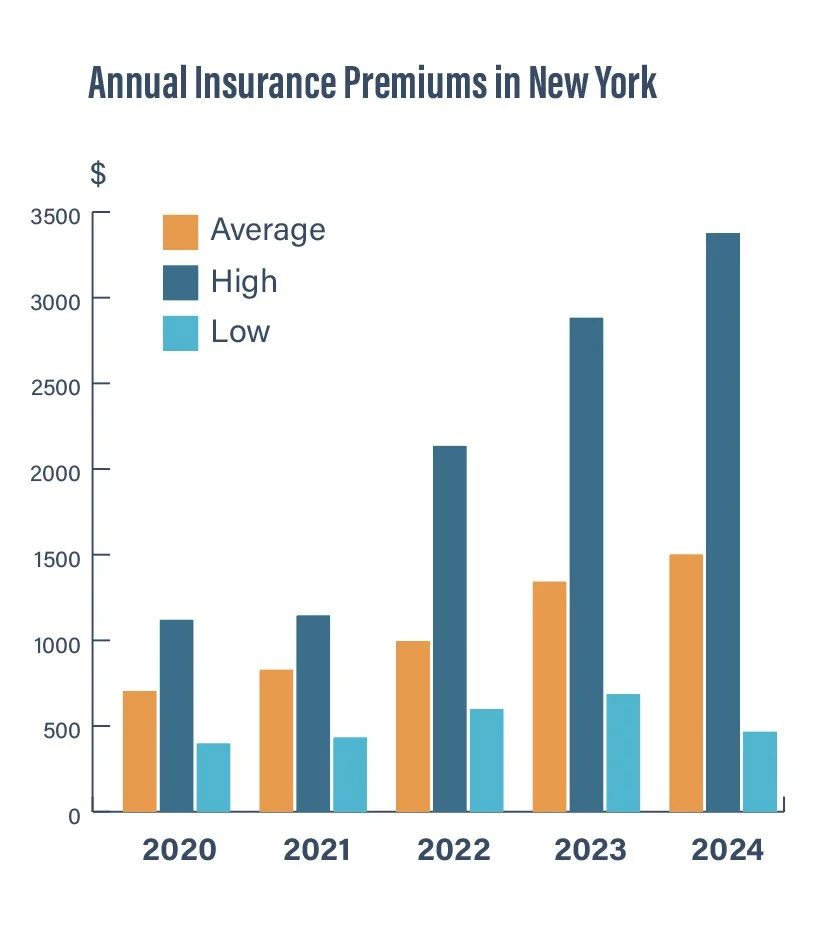

NYAA’s survey of over 60,000 rent-stabilized units revealed the scale of the disruption: total insurance costs rose 113% in just five years—from $703 per unit in 2020 to $1,501 in 2024. In The Bronx and Northern Manhattan, premiums climbed 134%, with some properties paying more than $3,300 per apartment per year. Insurance’s share of operating costs jumped from 5.4% to 8.2% in four years, far outpacing all other expenses. NYAA emphasized that these increases hit buildings regardless of claims history, reflecting broad market abandonment rather than property-specific risk.

Just as troubling, NYAA testified that 87% of owners have been forced to take on more risk, accepting higher deductibles or reduced coverage. Many now face deductibles five or ten times higher than before, shrinking umbrella coverage, and policies so limited that they no longer provide adequate protection. Meanwhile, insurers are pulling out: 74% of small owners were denied coverage, and every operator managing more than 5,000 units had at least one carrier refuse renewal. Common explanations included: “no rent-stabilized buildings,” “no Bronx buildings,” and “no NYC multifamily.” NYAA described a market collapsing under legal pressure, risk aversion, and structural failings that leave both tenants and owners exposed.

BRI’s testimony reinforced NYAA’s findings with regional data from Westchester, Rockland, and Nassau Counties. There, insurance costs rose between 22% and 67% over just two years, making insurance the fastest-growing operating cost and far outpacing utilities, maintenance, or labor. BRI connected these increases to climate-driven weather events, skyrocketing building material costs, and a broken reinsurance market that has pushed carriers out of older and lower-income housing stock entirely. Their members report that even “good risk” buildings are receiving double-digit increases and, in some cases, 100–200% hikes for high-limit policies.

SPONY’s testimony showed how the crisis is crushing small landlords, many of whom provide naturally occurring affordable housing. Owners of small buildings reported premium increases exceeding 37% in a single year; others saw liability premiums rise 95% or umbrella coverage drop from $100 million to $15 million. Many received only one last-minute renewal offer—sometimes requiring the entire multi-year premium paid upfront. SPONY emphasized that fraudulent personal injury claims, sewer-related flooding, and crime-driven underwriting restrictions add layers of pressure that small operators cannot absorb.

Across all three testimonies, a shared conclusion emerged: without intervention, escalating insurance costs will undermine the financial stability of New York’s most affordable housing. Their recommendations converged around the need for a state-backed reinsurance program, targeted tort reform, improved transparency, and incentives for resilience upgrades. Without these steps, they warned, New York risks losing the very housing that keeps the state affordable for working families.

II. DFS and HPD Testimony

The New York State Department of Financial Services (DFS) and the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) presented complementary but distinct perspectives on the state of the insurance market. DFS, as the regulator, sought to contextualize New York’s insurance dynamics within national trends. HPD, as the steward of the city’s affordable housing stock, emphasized the acute crisis unfolding within specific segments, particularly older and affordable multifamily housing.

DFS testified that New York remains “more stable than crisis states” like Florida and California, pointing to relatively low nonrenewal rates, a competitive market structure, and moderate statewide premium growth. However, DFS acknowledged significant stress within concentrated strata such as older multifamily buildings, supportive housing, and pre-war properties located in high-density or coastal areas. DFS cited four major national cost drivers—climate disasters, construction inflation, reinsurance volatility, and litigation costs—all of which filter into New York’s marketplace.

A repeated point of tension during questioning was DFS’s lack of access to claim-level data. Legislators pressed DFS on whether New Yorkers may be subsidizing losses in other states and how DFS evaluates catastrophe modeling submitted by insurers. Lawmakers also expressed frustration with the opacity of underwriting decisions and sought clarity on how insurers define “high-risk” neighborhoods.

DFS highlighted ongoing initiatives, including modernizing climate-risk modeling, enforcing anti-discrimination rules, implementing mitigation-discount programs, and deploying new budget authority to support affordable housing. DFS confirmed that its climate-risk guidance is intended to reduce long-term exposure and improve market stability—but acknowledged that mitigation benefits take time to materialize.

HPD’s testimony delivered a stark and urgent assessment: insurance costs are now among the most destabilizing pressures in New York City’s affordable housing sector. HPD reported that premiums across its monitored portfolios have nearly doubled—approximately a 94% increase—with some individual properties experiencing spikes of 300–500%. Liability insurance was cited as especially volatile. HPD noted that larger portfolios, including those using captives, fared somewhat better but still confronted system-wide escalation that outpaced operating budgets.

HPD raised concerns about potential discriminatory pricing patterns, including instances where buildings with Section 8 or voucher tenants were quoted higher rates or denied coverage outright. While HPD acknowledged the complexity of causal attribution, it emphasized the importance of ensuring that voucher holders are not indirectly penalized through insurance pricing.

Further, HPD described emerging climate-related risks, including new flood-insurance needs, rising extreme-weather exposure, and concerns about insurer withdrawal from coastal neighborhoods. HPD referenced resilience work in Mitchell-Lama buildings and urged state policymakers to integrate resilience funding, insurance reform, and capital programs.

In closing, both DFS and HPD underscored the need for greater data transparency, targeted interventions, and coordination across state and city agencies to stabilize the market and protect the long-term viability of affordable housing.

III. Insurance Industry Panel Testimony

Rising insurance costs and tightening availability in New York’s residential property market were the central focus of testimony delivered before the New York State Senate Committees. Representatives from the National Association of Mutual Insurance Companies (NAMIC), the American Property Casualty Insurance Association (APCIA), and the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) offered a unified explanation for the pressures confronting homeowners and insurers across the state. Collectively representing state regulators and the vast majority of the nation’s property insurers, the organizations argued that the challenges facing New York’s insurance landscape stem not from industry misconduct or cost shifting between states, but from deep structural changes driven by climate risk, economic conditions, legal system dynamics, and regulatory limitations.

The testimony underscored that New York’s insurance market remains both competitive and highly regulated. NAMIC pointed out that New York, despite its growing risk exposure, still ranks below the national average for homeowner premium levels. More than 230 insurers continue to offer coverage in the state, a strong indicator of market competition and consumer choice. APCIA reinforced this point by highlighting the New York State Department of Financial Services’ (DFS) rigorous rate-review procedures, which ensure that premiums cannot be excessive, inadequate, or unfairly discriminatory. Both organizations firmly rejected suggestions that insurers increase rates in New York to offset losses in other states. They emphasized that actuarial standards and state law require rates to reflect New York-specific loss experience, and DFS oversight makes cross-subsidization impossible.

Despite this strong regulatory environment, insurance costs are rising because the risks themselves are rising. The witnesses identified climate change and the increasing severity of catastrophic weather as significant drivers. According to APCIA, New York experienced ten billion-dollar disasters in 2024 alone, a stark departure from the historical norm of fewer than three such events annually prior to 2003. NAIC added that FEMA consistently ranks New York among the highest-risk states due to its dense development, valuable infrastructure, and exposure to hurricanes, severe storms, flooding, and severe winter weather. Catastrophe modeling shows that insured hurricane losses in New York could rise by as much as 64 percent under a 2°C global warming scenario. These escalating climate pressures require insurers to reassess risk and pricing more frequently and more aggressively.

Economic forces are compounding the problem. NAMIC and APCIA explained that inflation in construction materials and labor—up more than 40 percent in recent years—has dramatically increased the cost of repairing or rebuilding homes. New York’s housing market has also grown more valuable, with home values increasing 94 percent over the past decade. As the replacement cost of homes rises, so too does the insured value of those structures, resulting in higher premiums even for homeowners who have never filed a claim. These economic pressures leave insurers with little flexibility, as rising replacement costs directly impact the amount they must be prepared to pay out in the event of a loss.

Legal system dynamics further complicate the situation. NAMIC and APCIA highlighted New York’s unusually high litigation costs, driven in part by the Scaffold Law, the prevalence of nuclear verdicts, widespread fraud schemes—such as staged accidents—and the rapid expansion of third-party litigation financing. Nationwide, liability claims have increased by 57 percent over the past decade, a phenomenon often described as “social inflation.” These legal pressures are particularly consequential for older multifamily buildings and high-risk communities, where insurers face elevated exposure to costly claims. As litigation-driven expenses rise, insurers become more cautious in underwriting properties in areas where risks are already elevated.

Regulatory constraints also play a role. APCIA expressed concern that DFS’s lengthy rate approval process—averaging 233 days—prevents insurers from adjusting premiums in a timely manner to match rising costs. NAMIC noted that overly restrictive regulatory approaches can unintentionally destabilize insurance markets, citing California as a cautionary example. There, prolonged suppression of rate approvals eventually led insurers to withdraw from entire regions, leaving consumers with reduced options and limited access to coverage. The organizations warned that similar outcomes could occur in New York if regulatory frameworks do not evolve alongside changing risk conditions.

Despite the complexity of these challenges, NAMIC, APCIA, and NAIC converged on a clear solution: prioritizing resilience and mitigation. NAIC emphasized that mitigation is the most effective long-term strategy for stabilizing premiums, reducing losses, and maintaining insurer participation in high-risk markets. APCIA pointed to successful programs in Florida and Alabama, where home-hardening measures, stronger building codes, and community-level risk-reduction investments have reduced losses by 40 to 70 percent. NAMIC urged New York lawmakers to modernize statewide building codes, invest in resilient infrastructure, and expand incentives for homeowners and communities to undertake risk-mitigating improvements. These measures, the organizations argued, would not only protect consumers but also strengthen the stability of the insurance market as climate and economic pressures intensify.

Throughout the hearing, a clear tension emerged between lawmakers and industry representatives. Elected officials focused heavily on consumer protections, affordability, and transparency. They raised concerns about market consolidation, insurer withdrawal from high-risk areas, and the need to ensure that consumers do not bear the full burden of rising costs. Industry representatives, on the other hand, stressed the importance of understanding the structural forces driving risk and the need for regulatory flexibility so insurers can remain solvent and competitive in an evolving market.

A recurring theme was the importance of crafting legislation and regulatory reforms that avoid unintended consequences—such as reduced availability of coverage, increased premiums, or diminished benefits for consumers. The testimony made clear that while insurers and regulators share the goal of protecting New Yorkers, achieving long-term affordability and market stability will require not only greater resilience and mitigation efforts but also thoughtful regulatory modernization and legal reform.

IV. Nonprofit Housing Provider Testimony

In testimony from Enterprise Community Partners, the New York Housing Conference (NYHC), the New York State Association for Affordable Housing (NYSAFAH), and other mission-driven organizations—including S:US, ANHD, NHSNYC, LeadingAge, and public housing authorities—providers described an insurance market in crisis, one that is destabilizing thousands of affordable homes and undermining the state’s housing goals.

Across organizations, the data showed dramatic cost increases. Enterprise reported that insurance expenses for 37,000 affordable units have grown by 110 percent since 2017, while NYHC documented a 103 percent increase in premiums for affordable apartments between 2019 and 2023. NYSAFAH and supportive housing providers described even sharper rises, with some portfolios experiencing jumps from $6 million to $16 million in three years. Many testified that insurance now consumes between 16 and 22 percent of gross rents—levels incompatible with long-term affordability requirements and unmanageable within statutorily limited rent structures. As a result, more than half of affordable housing developments in several datasets are now running operating deficits, with depleted reserves, delayed capital repairs, and heightened risk of loan noncompliance.

Providers explained that these pressures stem from multiple structural forces. Climate-driven disasters have increased the cost of reinsurance, which carriers pass on to landlords. Construction inflation has pushed up the cost of rebuilding, directly affecting premiums. At the same time, nonprofit owners reported being pushed into the surplus lines market, where coverage is narrower and exclusions common—particularly for risks like mold, lead, and assault-and-battery that disproportionately affect buildings serving vulnerable populations. Lenders are increasingly alarmed by weakened coverage profiles, flagging many affordable buildings as higher-risk loan candidates.

New York’s liability environment compounds these challenges. Providers across all testimonies cited the state’s absolute-liability Scaffold Law, escalating slip-and-fall litigation, nuclear verdicts, and opaque third-party litigation funding as drivers of rising liability costs. These pressures land especially hard on supportive housing providers whose buildings serve seniors, people emerging from homelessness, and residents with higher medical or service needs. Several organizations warned that the volatility of liability insurance threatens funding streams tied to health and human services contracts.

Throughout the hearing, nonprofits emphasized that they have few options. As affordable housing providers, they cannot raise rents to cover rising costs. Cutting services undermines resident stability, and drawing down reserves jeopardizes long-term preservation. Some organizations explored captive insurance models but cited high capital requirements and regulatory complexity as barriers.

To address the crisis, providers converged around a set of policy priorities: a state reinsurance backstop or affordability relief fund; financial incentives for building safety investments tied to mandated premium reductions; data-transparency legislation such as annual DFS/HCR reporting; targeted liability reforms; anti-redlining protections; and expanded resilience funding for climate risks. Many stressed that the crisis disproportionately affects low-income communities and buildings serving people of color, reinforcing existing inequities.

In sum, nonprofit providers framed New York’s insurance crisis as an immediate and existential threat to affordability, safety, and long-term housing stability—one that requires swift legislative and regulatory action.